How to Reduce Risk of Injury

Imagine a life without stress. No work to do, no relationships to manage and no goals to fail or achieve. It may be a stress free life, but it’s not a life to aspire towards. Now imagine a life with a great deal of stress. Thousands of people or millions of dollars affected by the decisions you make, traveling from hotel room to hotel room, managing family relationships, trying to parent children while being at constant risk of losing your high status. The life with more stress may be more eventful, more fulfilling or more lucrative, but it’s unlikely to be sustainable. It may lead to burnout or even worse health outcomes like stress-related chronic diseases.

We can do the same thought experiment with physiological stress such as exercise. Not enough exercise and you may become frail or overweight. Too much exercise and you may suffer from injury or other long-term problems later in life that restrict you from activities you may cherish. Whether you’re managing work-life balance or trying to prevent injury, monitoring and maintaining the right amount of stress is integral to sustainably achieving your goals. This article seeks to establish a framework for injury and helpful practices for preventing “preventable” injuries in the short-term and encourage better long-term health.

A framework for injury risk

First, let’s establish what is meant by preventable short-term injuries. Some injuries cannot be prevented without foresight—stubbing a toe or sustaining a bruise often occurs because we weren’t aware of the risk in the first place. But other common athletic injuries such as a hamstring strain or a sore back arise from overuse or lack of training and are more preventable. Relative to short-term injuries, a long-term injury or condition is more chronic in nature and may be influenced by reoccurring short-term injuries or lifestyle choices. In many cases, long-term conditions are also preventable; examples include osteoporosis, arthritis and general declining fitness. Risk of short-term and long-term injury can be tempered by a life of mindful and consistent exercise.

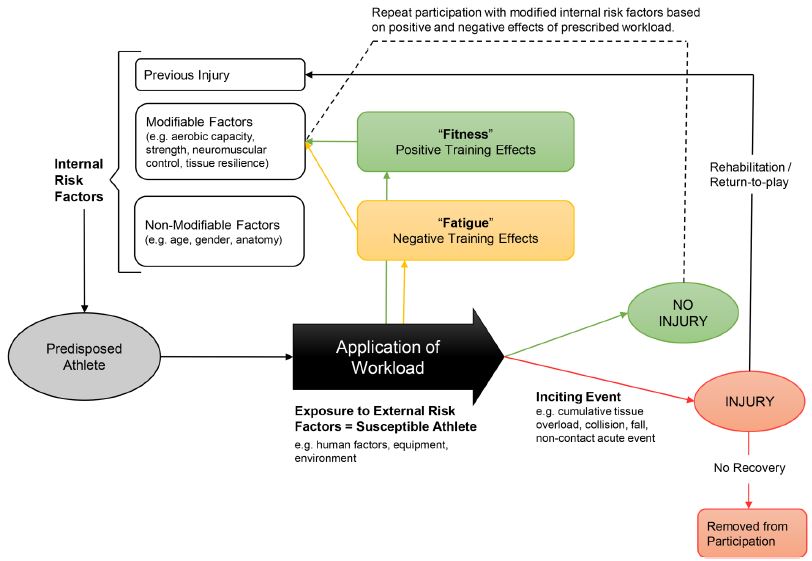

The cause of injury is multifaceted and is summarized in the workload—injury aetiology model presented by Windt and Gabbett (2017) shown below:

This comprehensive cycle can generally be summarized by the following elements:

1) Exposure: external factors which lead to the inciting event which causes the injury

Example: Participation in a competitive basketball game with friends which led to the injury

2) Fitness: internal factors which are either positive adaptations which decrease risk of injury or lack of adaptations which increase risk

Example: An avid weight lifter may have greater ability to withstand load and lower his injury risk

3) Fatigue: internal factors which can be thought of as the body’s response to the exposure or exposure over time. Greater fatigue is associated with greater risk of injury.

Example: You may be more likely to have an injury in your third basketball game in three days vs. your first or second game.

Out of the three elements above, fitness and fatigue are the most important elements to focus on when considering factors you can influence to mitigate risk of injury. Fitness is an important part of our body’s resilience to physical stressors and at the center of injury prevention. Aerobic capacity, skill level and body composition all play a role in determining our likelihood of being injured and can all be improved through fitness. Fatigue can be broken down into two separate levels: (1) the tissue level and (2) the athlete level. Tissue level fatigue refers to the excessive “microdamage” which occurs at the tissue level when a tissue is being exerted beyond the load it can take on. This can be further encouraged if there is insufficient recovery time for tissues between activities. A common example of tissue fatigue occurs in long-distance runners. These athletes apply stress to their bone tissues for a sustained period of time resulting in cellular breakdown (microdamage) and reconstruction. However, if the athlete runs more frequently than the cells can be reconstructed, a bone stress injury can occur resulting in severe pain. At the athlete level, things operate a bit differently. Fatigue at this levels results in loss of coordination and decision-making ability. This type of fatigue can result in “sloppy work” and lead to injuries caused by unstable joints and overall lack of concentration.

What is interesting about this framework is the inter-relatedness of the different elements. With low fitness any exposure can be risky. Even with good fitness, too much exposure can result in fatigue. Additionally, training for better fitness itself is a tricky endeavor as it will frequently be accompanied with fatigue and needs to be managed with more general exposure. So the question becomes, how do I balance fitness and fatigue with proper exposure?

Four steps to reduce injury risk

1) Ask yourself, what am I training for?

The first step to reduce injury is to set-up training and condition appropriate for the type of activity you’ll be doing. Training for walking around Disneyland with your kids will require a different plan than training for high intensity bike rides. Establishing your athletic goals will help with designing a training regime which is most appropriate for the types of activities you engage in.

2) Ask yourself, what are my risk factors?

Important internal risk factors in addition to fitness and fatigue include sleep patterns, high stress levels, travel frequency and diet. Certain lifestyle factors such as limited sleep can greatly increase your risk of injury because of reduced recovery time and greater fatigue. More obvious risk factors to consider are previous injuries and prior history. However, regardless of whether a risk factor is psychological or purely physical, monitoring them and actively working on them will help reduce risk of injury.

3) Set-up a training schedule and keep a training diary

Training to run 26.2 miles starts with running one mile; a good training schedule will gradually increase exposure avoiding spikes until your desired performance level matches training intensity at a 1:1 ratio based on research shown below by Tim Gabbett in 2016.

Research shows that tracking your training with a diary or app can encourage more consistency and pave the way for gradually increasing intensity over time.

4) Recover like you train

Even if you are training perfectly according to plan and monitoring your risk factors well, injury risk will always be high if you haven’t allowed for good recovery. Recovery is more than just rest, it includes proper nutrition and hydration, emotional encouragement and active rest.

Taking steps towards addressing all of the elements listed above will help reduce injury risk in the short-term and facilitate a long and active lifestyle—preventing risk of long-term chronic conditions as well.

Injury free?

Activity comes with risk of injury, but no activity guarantees illness in the long-term. Not only is activity worth the risk but the most common injuries can be prevented. While you’ll unlikely be injury free all the time, there are simple things you can do that can decrease risk of injury. A thoughtful training regime will increase conditioning and proper recovery will protect against fatigue allowing for a more active and healthy life over the long-term.

References

Windt J, Gabbett TJ. How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload—injury aetiology model. Br J Sports Med.2017;51:428–435.

Gabbett TJ. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med.2016;50:273–80.